Mini Living – 29.10.19

Invert 3.0. green magazine will curate a speaker series which will be held in conjunction with an exhibition of 1:20 scale models to discuss relevant architectural topics.

This Northcote site represents a typical Australian block. The delicate Victorian formality of cast iron lacework and detailed timber façade, subverted by living room furniture and upturned milkcrates extending living spaces to the street. Sofas on the porch were once a sign that a suburb is going to the dogs, now we call it street activation and wash it down with a good dose of nostalgia.

Any enthusiasm for gardening in the front yard runs out of puff as the back yard extends past the concrete runway to the quietly rusting hills hoist. Beyond a no-man’s land of abandoned veggie patches, long grass, a remnant slab outlining a long-gone shed and maybe an incinerator. This yard is too large to manage for many in our busy lives and it takes an awful lot of water to look after that lawn.

Fingers of vegetation form soft arbours reaching across the laneway from behind paint pealed layers of corrugated fencing and flattened oil tins.

We considered the position of the site at the intersection of the wide and narrow lines of Hoddle’s 1837 grid that provided service access to the rear of the Victorian cottages.

We noticed the flow of surface water, evidenced by cushions of moss growing thickly in the dampness between the bluestone.

We thought of the earth beneath these heavy, smooth-worn cobbles and the underlying geology which we glimpse through prosaic soil tests. Digging deeper to something we should know more about, the land itself and the custodians of this place, the Wurundjeri people.

This design adds another layer to this place that speaks of our society today. One beginning to acknowledge our resources are finite and the need to densify to reduce our carbon footprint and the impact of our habitation on the earth.

Big changes won’t happen without serious reconsideration of planning schemes. Dwellings without carparking are nothing new, nor is building to the boundary. What is new is to screen windows and balconies so that we don’t know if anyone is home, and don’t achieve passive surveillance. Vehicular access to properties via laneways renders them unusable for most else. Garage doors and turning indents make them unsafe. Laneways could form networks of rain gardens to harness water that flows here already, slowing peak run-off through the stormwater system to the creeks, river and ultimately the Bay.

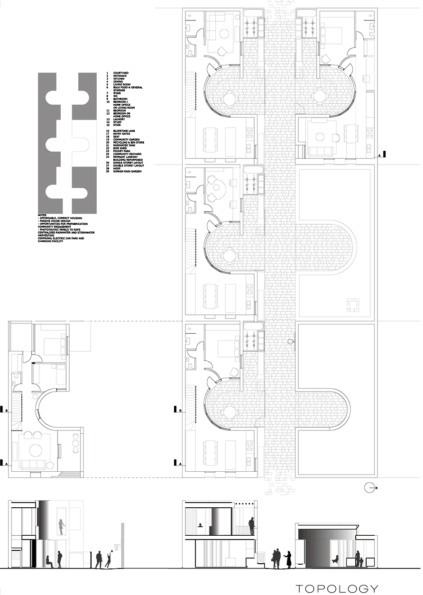

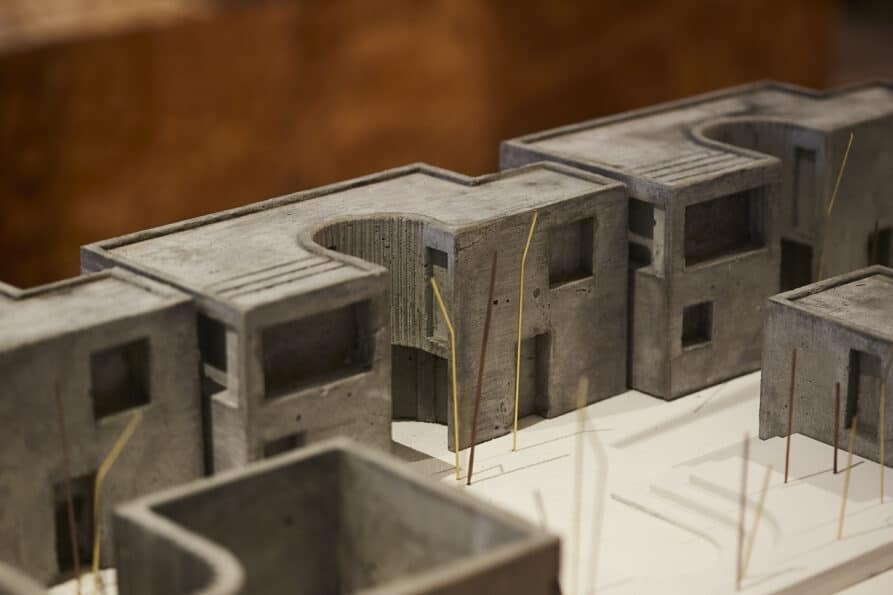

Our design is a site specific and simultaneously an example of a typology that might be replicated with individual elements, single or double story houses, adaptive reuse and pocket parks, interchangeable, depending on specific site conditions. Like Victorian housing, rooms are not prescriptive and are as varied as their inhabitants. There are no walk-in robes or ensuites. There is flexibility and opportunity.

The site is re-orientated to address the lane, with courtyards and living spaces open to the shared space, extending on either side of the lane and into pocket parks. Vegetable patches and gardens that blur the division of private and public land are gesture of generosity and neighbourliness.

Like a London Mews, pedestrians are prioritised, children can play safely beyond their gates and people drink coffee on their front porches.